I believe that closed-source, proprietary clinical software is fundamentally unethical, going beyond even the pharmaceutical industry in how closed source clinical software subverts the duty to share medical knowledge, and protects intellectual property to the detriment of patients.

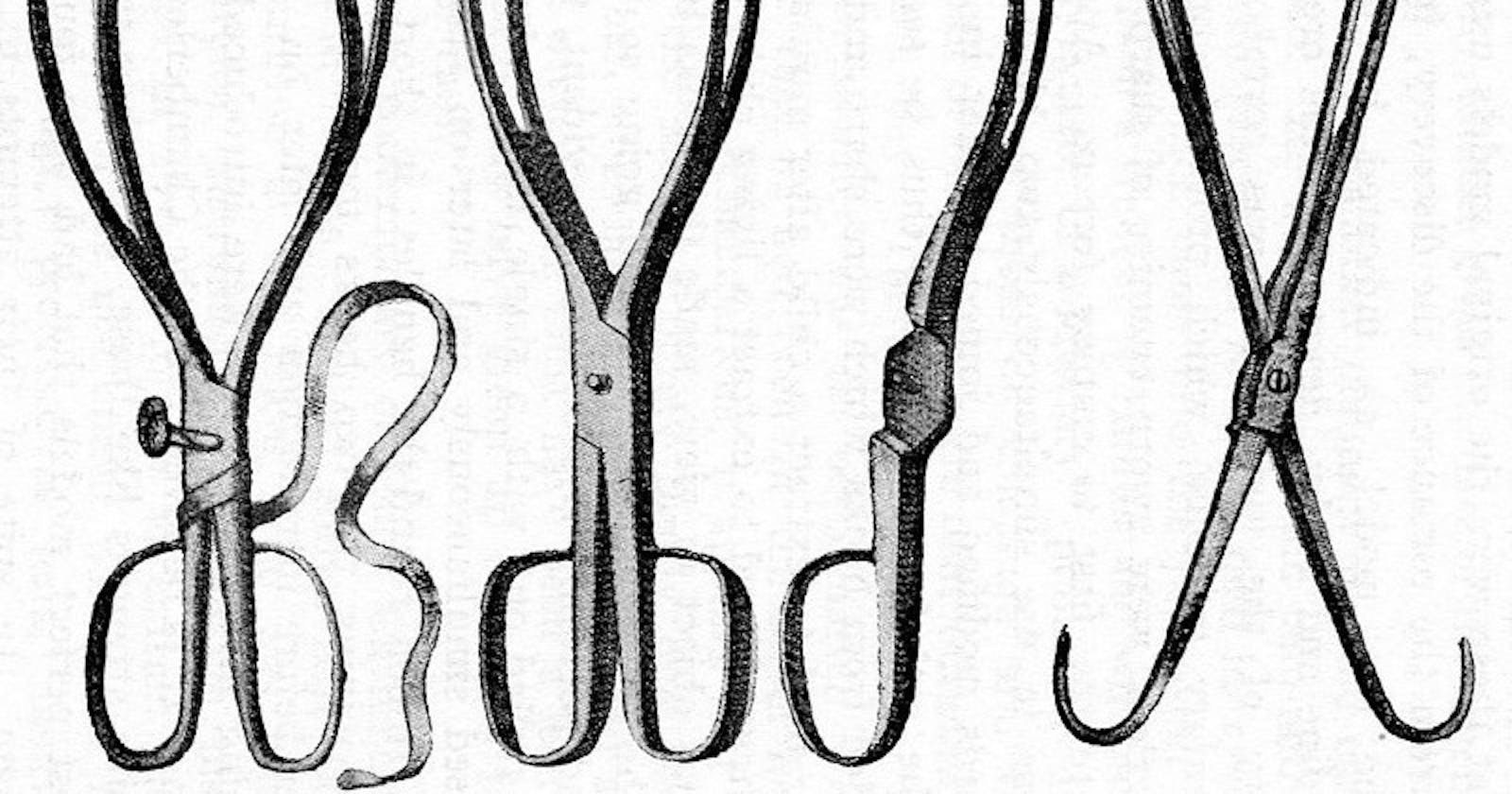

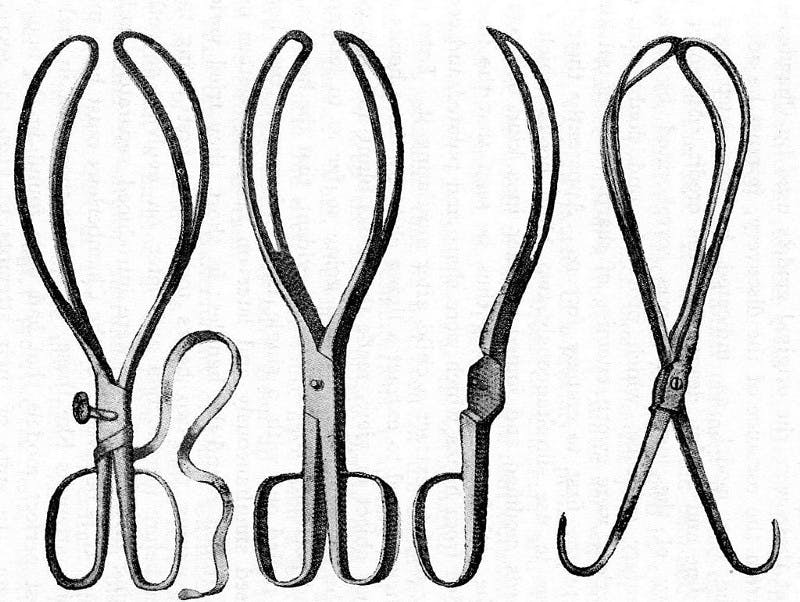

Chamberlen forceps (image credit: public domain via Wikipedia)

When developing healthcare software it is important to recognise the additional ethical dimension that medicine brings with it. Medicine affects all human life in such profound ways that we need to consider the moral dimensions of its technological developments in a completely different way to that of other industries:

In other areas of human endeavour, for example, there is usually more choice available to the consumer — including, often, the choice to opt out of use of that technology. People cannot ‘choose’ not to need healthcare.

Further, the consequences to an individual of being denied access to the best available treatment may well include physical harm, early death, unnecessary pain, avoidable disability, and many other unpleasant and potentially permanent disadvantages.

Medical Software now IS Medicine

Not long ago, clinical software consisted of simple systems for patient administration, databases for recording clinical information, and messaging. Nothing particularly exciting, and nothing particularly likely to make huge differences to clinical outcomes. One can easily see how these dull systems weren’t considered to be ‘part of medicine’ and not thereby subject to the scientific process and moral obligations of a medical innovation.

Now, however, we have a range of complex interactive clinical systems which have become so integral to the delivery of care that it’s likely that a good system could positively influence clinical outcomes (and conversely, a bad system could cause harm!). We have disease-specific scoring systems, clinical algorithm implementations, clinical decision support, patient-facing and clinician-facing mobile apps, triage engines and much more. These things can certainly influence clinical outcome. Yet they are in most cases closed-source, proprietary, non-peer-reviewed, and not independently testable.

Looking to the future, we’re promised that ‘just around the corner’ (I’m sceptical, can you tell?) is an #AIrevolution in which machine learning algorithms (not actually AI, because that doesn’t yet exist) will be able to make clinical decisions. The business model of these algorithms is always based around a closed-source, proprietary, profit-making model. Often there’s a venture capital-based funding model which further distorts thinking around the intellectual property.

But, with these closed-source proprietary systems, there’s no way to independently test their claims, there’s no scientific process, and the need for proper clinical peer review has been completely over-ridden by the wish of the company to make profit.

As software and technology have become more and more part of medicine itself — neither distinguishable or separable from the practice of medicine — we must consider that these software artefacts now have to become part of the corpus of medical knowledge, and thus there is an ethical duty to share these technological artefacts openly, as Open Source software and Open Hardware, in order for the maximum benefit to humankind.

Increasingly, software is being developed which — through whatever mechanism such as reducing error, improving clinician information presentation, decision support etc — has the inherent capability to reduce suffering and save lives, and in such circumstances it is unethical and immoral not to be able to openly share such innovation with the world. The model of open-source software provides a clear platform for such sharing.

Indeed it is hard to imagine how clinicians involved in healthcare innovation could argue against the open-sourcing of this work without it coming into conflict with their responsibilities as a medical professional. If you are a clinician involved in software development, let me ask you: how are you justifying the restriction of that intellectual property to only those patients who can pay?

Medicine Was Open First

Medicine has historically always been an ‘open-source’ profession, even before the term open-source came into being. As an ancient profession, doctors have had ample opportunity over the millennia to experience the dangers of quackery, alchemy, and witchcraft which are the unavoidable sequelae of a lack of open sharing and open peer-review of developments in medicine.

The earliest medical pledge, the Hippocratic Oath, contains in its second paragraph a clear knowledge-sharing commitment — to teach the next generation of doctors ‘without fee or indenture’ (although it stops short of recommending openly sharing the secrets of the medical arts such as sharing with non-doctors)

The Declaration of Geneva, which is the internationally-ratified successor to the Hippocratic Oath, makes this knowledge-sharing responsibility even clearer:

‘I will share my medical knowledge for the benefit of the patient and the advancement of healthcare’. — Declaration of Geneva

So it’s clear in historical precedent that medical professionals have a duty to share medical knowledge with their peers (I’m including all clinicians under this ethical umbrella — even ones who do not take the Declaration of Geneva or the Hippocratic Oath)

Closed Source subverts the Scientific Process

Let’s try a thought experiment. If I was to announce that I had developed a new medicine, or surgical technique, or lab test, which I claimed had clinical benefits, then in order to be taken seriously I’d have to be able to prove that.

Imagine I had a new surgical technique which I say definitely saves lives. But I’m not telling you how. I offer to come to your hospital and perform the operation, the anaesthetist will be blindfolded, the patient will be asleep, and all other staff are sent out. Nobody can observe my secret surgery. I perform the operation, take my fee and leave.

I would be laughed out of the profession for this. Without publishing my new surgical technique nobody will believe my claims of ‘saving lives’. It would be dismissed a pure quackery. Without publication there can be no peer review. And without sharing this knowledge I deny this benefit to the majority of the world. I cause suffering and early death to those denied my proprietary surgical technique. In medicine this would and should be completely unacceptable.

But if you replace ‘surgical technique’ with ‘clinical software’, I’m fine.

Using closed-source software subverts the scientific process by preventing researchers from fully inspecting the intervention they are trying to study.

Medicine nowadays is a relatively conservative profession, deliberately slow to jump onto the latest exciting technological trend, for very good reasons — much of the harms of the latest tech is not immediately apparent, and may take decades to be obvious. After radiation was discovered in the early 20th century, an incredible array of quack cures sprang up — radium and radon as a general tonic, X-rays to treat TB — only for the appalling harms of radiation to become apparent in the decades to come.

In order for the benefits and harms of a new intervention to become apparent it takes careful adherence to the scientific process, repeated studies, replication and extension of existing studies, and most importantly: complete access to the thing you’re studying. It’s hard to study and understand a ‘black box’.

So, what happens when medical innovations are kept secret?

History gives us a particularly appalling demonstration of the human consequences of secret medical treatments — the Chamberlen family of obstetricians — who for around 150 years kept secret their development of obstetric forceps. During the time that the innovation was kept hidden from the rest of the world, it is likely that hundreds of thousands of mothers and babies died as a result of the lack of this treatment.

Their secret forceps were found by accident hundreds of years later, and it was only then that it was realised how the Chamberlens had been delivering babies, using their proprietary technology, for the exceedingly rich and Europe’s royal families only.

It is because of such precedents that modern healthcare interventions are required to be openly published in peer-reviewed journals before they are taken seriously, indeed it would be unthinkable in the medical profession to offer a ‘secret’, unpublished intervention which was not openly published and its principles understood. To do so in the modern medical world would risk professional ridicule and the wrath of medical regulatory bodies, and would possibly even be a basis for criminal charges in some circumstances.

Open source for quality, safety, and speed.

Sharing knowledge means reduced duplication of effort — if knowledge is freely available to me as a clinician I don’t need to use my resources to create it all over again. Instead I can use my resources to create new knowledge which I can then also share, meaning we all benefit from two interventions rather than one. We all progress faster.

Open publication of medical innovations is the only way to obtain independent scrutiny of experimental results, which helps us ensure that assertions of clinical efficacy are supported by evidence. Without this, we simply have to rely on the assertions of the owners of the technology that the intervention is clinically safe and efficacious.

Open publication allows for continuous, iterative development of an existing technology —for example, another team’s refinement of a published surgical technique in order to reduce risks or improve outcomes — but in the case of closed-source, proprietary software this iterative development simply cannot happen. The copyright owners have exclusive control of the direction of development, and indeed whether development happens at all.

Public Money, Public Code

Quite a large proportion of medical research is publicly funded. This is taxpayers’ money which is used for developing medicine. Where this medical research results in development of software, data sets, algorithms, or any other technological feature, it’s imperative that these be open sourced, so that the the maximum taxpayer benefit is extracted from the investment.

The Free Software Foundation of Europe’s excellent Public Money, Public Code campaign extends this beyond clinical software to all publicly funded software. I agree.

In writing this section, it made me think about the parallel silly situation in clinical research: content is given to medical journals for free, which they then hide behind a paywall, denying access from the very people whose taxes paid for the research. That’s another story, but it’s related and highly pertinent in terms of the revolutionary effect that the Internet has had on traditional publishing and software development models.

Crimes Against Humanity

Ok, here we come to perhaps the bit where I’ve gone too far with my hyperbole. You decide. But I believe that based on all of the above argument, closed source clinical software is a crime against humanity.

(Bear with me)

Think: If one developed a clinical innovation that provably saves lives, then as a doctor one is duty-bound to share that knowledge, such that as many people as possible can benefit from that worldwide.

By denying it to people who can’t afford it, forever, I’m harming those people who can’t access that technological wonder.

“Aha”, you’re about to say, “what about drugs? — the pharma industry denies access to its latest drugs, patents them, charges for them, denies them to those that can’t afford them. And the medical profession goes along with it, even joins in with it!”

You’d be right — it’s deeply unethical — but even in the pharmaceutical industry, their limited patent or exclusivity right has a relatively short life, a fixed duration after which the drug becomes generic, and anyone can make it, meaning expensive proprietary drugs become cheap and widely available with a decade or so of their inception. (And as an aside, you probably shouldn’t be using “well the pharmaceutical industry does it” as a defence of a moral standpoint under any circumstances.)

The pharmaceutical industry has yet to come up with any alternative business models that allow them to ‘recoup’ research and development costs (plus several thousand percent) — without having a period of exclusive production.

But in the case of software, we do have alternative business models: SaaS (Software as a Service), provision of core services around the free software itself, development of custom functionality, integrations, data migrations, feature plugins, apps, security testing, hosting, warranty provision, user support and much more. There’s plenty of ways to make a perfectly good business around an open source product. And because of the collaborative development, the R&D costs can be shared across a huge open source community, rather than being a burden on a single entity.

With software, replication of the original costs almost nothing, so there’s simply no reason not to share these developments with everyone that wants them, as libre software.

Complicit….

As I make all these assertions about how clinical software should be developed and shared, and very hyperbolically state that who impede open sharing of clinical software may be committing crimes against humanity, I’m also aware that there are some among the medical profession who are complicit in this process of closed-sourcing medicine and developing proprietary clinical interventions.

As I asked earlier in this article, I ask again, how do those clinicians justify their involvement in the closed-source, proprietary software that they are developing? Without independent peer review it’s impossible for them to know if they are actually doing good or harm with their intervention, and — if their intervention IS actually doing good — then by keeping the intervention secret they are just as guilty as the Chamberlen family.

I propose that the clinicians and the medical community should actively take steps to prevent the further ‘proprietorization’ of medicine, and going forward we should insist on Open Source software for all of medicine.

We must educate other clinicians in open source software, and advocate openness in all areas — open governance, open algorithms, open standards, open data, and open organisations.

This article is a development of my original talk ‘Open Source Is The Only Way For Medicine’ — the slides for which are (openly) available here (source code)